Misunderstood Landscapes: Rivers

How widening our view of land, water, and time can help us be better river keepers.

The woody trail paralleling the river is dappled in early morning sunlight that shifts and moves amid dancing leaves. But between the maple and sycamore, I catch glimpses of churning brown water. It’s moving fast, bearing broken branches and sediment toward Lake Michigan.

This late in the season, birdsong has softened to quiet chittering, barely a whisper. But the further I walk, the fewer I hear. It’s strangely quiet and despite the pleasantness of the day I know something unusual has happened here. The goldenrod and jewelweed on either side of the trail have been flattened sideways, stems pointing downstream. Their leaves are tattered and caked in dry mud. Branches well above head height support long strands of dead grass that hang there like tinsel. Further along, I find several uprooted boxelder trees blocking the trail. I scramble over the fallen trunks only to find an impassable, washed-out bridge. Each end hangs limply over a ditch of oily grey water.

This urban greenway, minutes from my home, is a familiar and beloved walking route and local wildlife corridor, but today it’s almost unrecognizable.

Several weeks ago, Milwaukee endured record rainfall. Within a matter of hours, roads and rivers flooded, stranding people in their cars. The State Fairgrounds had to be evacuated. Photos showed people fleeing in knee-deep floodwater. Entire parks were submerged.

Evidence of the flood’s force and magnitude is still present all around me. The waterline—the crisp, dry mud and the grassy snags—is above my line of sight.

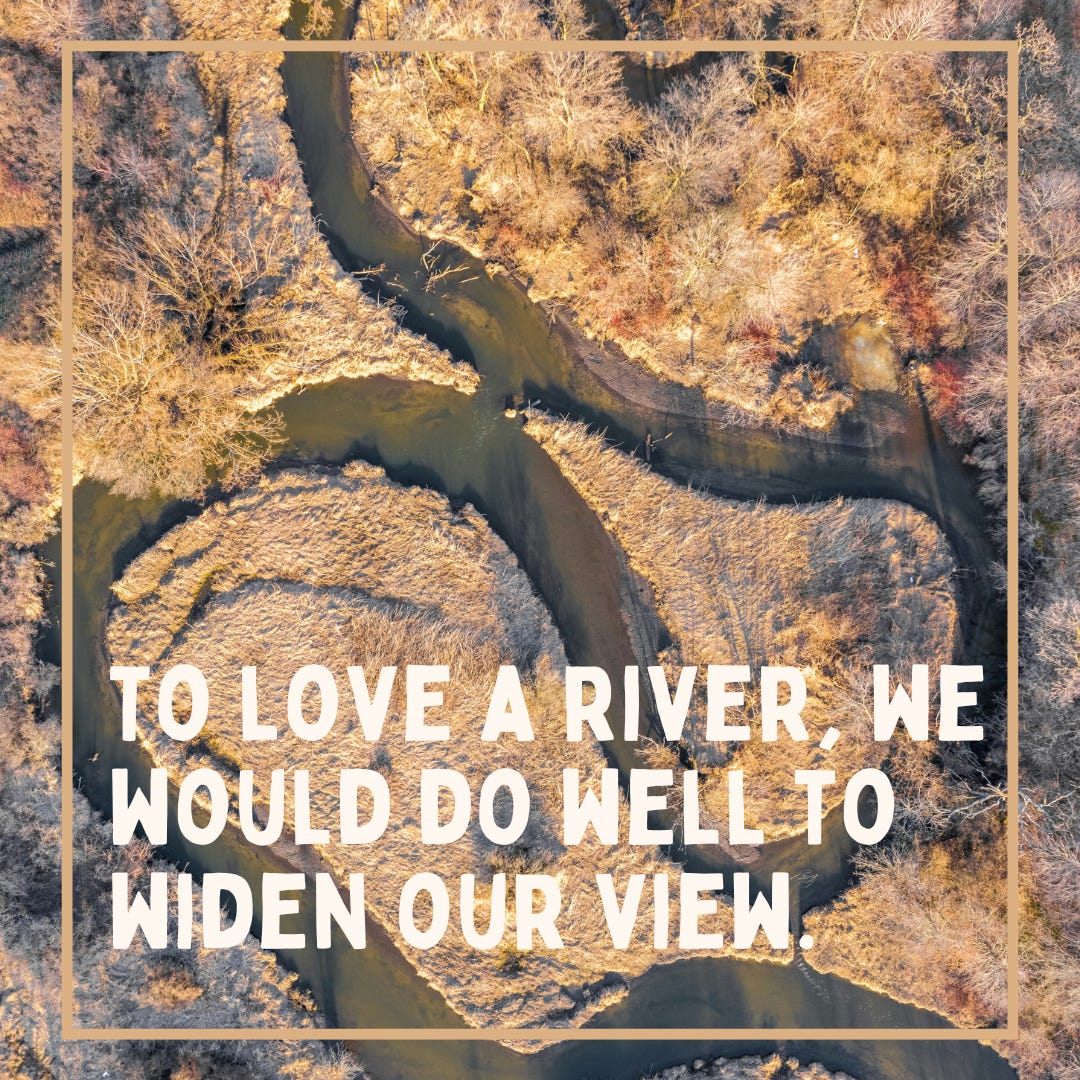

People wrongly assume that where a river flows today is where it flowed in the past, that these moving bodies of water are a fixed part of the landscape. In truth, unimpeded, naturally flowing rivers can wriggle and shuffle like snakes over flat land. They can carve ever deeper trenches and widen caves, making more space for themselves. They broaden and narrow in response to weather conditions and human activity. They will search out new paths of lesser resistance. Given enough time, rivers will even migrate. Were we to look into the past, we would find evidence that rivers have abandoned their old routes altogether or even changed the direction of flow. Unfortunately, in our now-centric culture, we fail to give due attention to what came before.

In America and elsewhere, we have grown so accustomed to the damming and channeling of rivers that few people know what a freely flowing river looks like, let alone understand how one behaves. Here in Wisconsin, up until the late 1800’s rivers still chose their own course and flooded seasonally, distributing mass quantities of sediment across their floodplains, creating some of the most fertile, biodiverse lands on earth. Because humans wanted to live on riverbanks and along waterways and wanted to take advantage of the rich soil for their crops, they decided it was safer to commit rivers to a prescribed course. Since then, we have built increasingly complex and technologically advanced systems aimed at overcoming two of the most essential predilections of rivers: to move, and deposit soil-enriching sediment.

Our rivers have been heavily modified, and the hand of development has been hard-hitting. Rivers around the world have been dammed, channeled, drained, and polluted. But rivers are just one part of a complex ecosystem that transports water across land. Before water reaches a river, it will often pass through a series of unique ecosystems known as wetlands.

Wetlands are like immense reservoirs that link land and water. The term “wetland” refers to a suite of diverse habitats, including marshes, fens, swamps, sedge meadows, ephemeral ponds, bogs, and quite a few others, depending on the type of hydrology, soil, and vegetation it supports.

Wetlands also happen to be essential for maintaining river health. They mitigate flooding by capturing and storing water, prevent erosion by slowing the passage of water, and decontaminate water by removing pollutants and sediments, keeping our lakes, streams, and drinking water clean. Yet despite their essential role in maintaining the health of the land and its waters, wetlands were and continue to be undervalued by colonialists and their descendants. In less than 200 years, most of the wetlands in the United States have been lost to development and farmland. Loss of a single wetland not only affects wildlife diversity and distribution, it changes how water travels across a landscape and enters our rivers.

Wetlands act as natural filters, removing sediment and absorbing excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus from runoff before it reaches rivers. This prevents harmful algal blooms and improves overall water quality downstream. They also absorb and store large volumes of water during storms, which slows the passage of water, lessening the severity of flash floods. Conversely, by slowly releasing the stored water during dry periods, wetlands help maintain streamflow, preventing rivers from drying up during droughts.

Although climate change is undeniably contributing to extreme weather events, increasing their frequency and severity, the modifications we have made to our landscapes are exacerbating the damage. By removing the natural features of rivers to suit our own desires and preferences, they no longer function as they should. This leaves rivers less able to respond to the pressures of climate change and more prone to catastrophic flooding.

Wendell Berry famously wrote, “Whether we and our politicians know it or not, Nature is party to all our deals and decisions, and she has more votes, a longer memory, and a sterner sense of justice than we do.” Yet rarely is it the policy and decision makers who are among the first to fall victim to climate-driven devastation. Biblical floods are now a yearly event but as with most environmental problems, their destruction often hits poor, rural, and Indigenous communities hardest. Claiming to be apolitical in a time of climate emergency is an admission that one benefits from the safety and entitlement of an unjust system. We must all raise our voices together above the din of the rushing river if we hope to recalibrate and stabilize our rapidly deteriorating life support.

For too long we have underappreciated the immense power, individuality, and vulnerability of our rivers. Understanding the intricate interconnectivity of waterways may be the first step to honoring what was once held sacred: the life-giving and cleansing properties of water. Where I live, in Milwaukee, three rivers—the Milwaukee, Menomonee, and Kinnickinnic—converge at a wide outlet to Lake Michigan. Pausing to consider how far those waters have traveled, all the lives—both human and non-human—they have enriched on their long journey, can instill a sense of humility and contribute a degree of reverence to the act of noticing. Cultivating a deep respect for earth’s natural wisdom and processes takes it a step further, helping to diminish our sense of self-importance and superiority.

Riverkeepers know that to improve degraded rivers and restore them to health we must often unpick the influence of past humans, a process not unlike untangling wire from a snag on a riverbank, a tough but necessary part of healing. Engineering solutions once meant to protect people from a river’s fury and floods now intensify the effects of extreme weather events. Conversely, removing dams, concrete channels, rubbish, and other pollutants helps return rivers to what they once were: dynamic ecosystems upon which thousands of species depend. In places where a channel cannot be safely removed, as in highly developed urban areas, planting aquatic grasses and adding structural elements that mimic features of natural rivers that slow the passage of water, provide surface area for plants to grow on and shelter for animals, can help improve water quality and river health.

I’m meeting a friend further up ahead, beyond the mangled bridge, so I step off trail. Other feet have already trampled the mounds of invasive reed canary grass, seeking passage. The long grasses are damp with dew and hang heavy, like wet hair over the shoulders of the riverbank. I marvel at the resilience of these plants that withstood the fast-moving floodwaters, accelerated here by the narrowness of this stretch of river.

Before long, my shoes are soaked with dew, all the way through to my socks. By the time I make it back onto the trail, my pantlegs are wet too…and decorated by a few new ornaments! Tiny slugs and snails have brushed off the grasses and now cling to the fabric. Where were these slow-moving creatures during the floods, I wonder? When mature trees succumbed, it’s a marvel to think these tiny beings somehow avoided getting swept away by the vicious current. I gently remove them, one by one, and continue on, navigating washouts and sidestepping rubbish dangling from trees.

In my quest to connect people with nature, I often begin with a question: how do we teach people to love a river, a prairie, a sand dune, a wetland—and by extension all the beings that rely on them for survival? Key to the solution is building relationships with these places by spending time with them. We are more likely to defend the forest where we jog, the riverside trail where we cycle, the lake where we learned to fish, or the bluffs where we sit and read. Places become meaningful to us as we get to know them, as our memories of visiting these places—the experiences we have there, alone or with others—infuse them with meaning. Giving attention to how the seasons alter these landscapes, which plants and birds are present or absent during each new month of the year, these ways of noticing add nuance and depth to our relationship with land and water.

To love a river, we would do well to widen our view. Rivers not only run over vast distances, they change drastically over centuries-long timescales. Nor can they be viewed as isolated individuals. They exist within a network of relationships with other habitats, including wetlands, lakes, streams, and more. Rivers are so much grander than the span of water we see when we stand on their banks. From that limited point of view, a river challenges our spatial and temporal awareness, asking us to reject outdated and imperfect notions of isolated environments and replace them with much more meaningful relationality.

Another great piece Em, with lots to think about. It touches on so many other aspects of our daily experience during which we overlook or ignore the world around us which sustains our very existence.